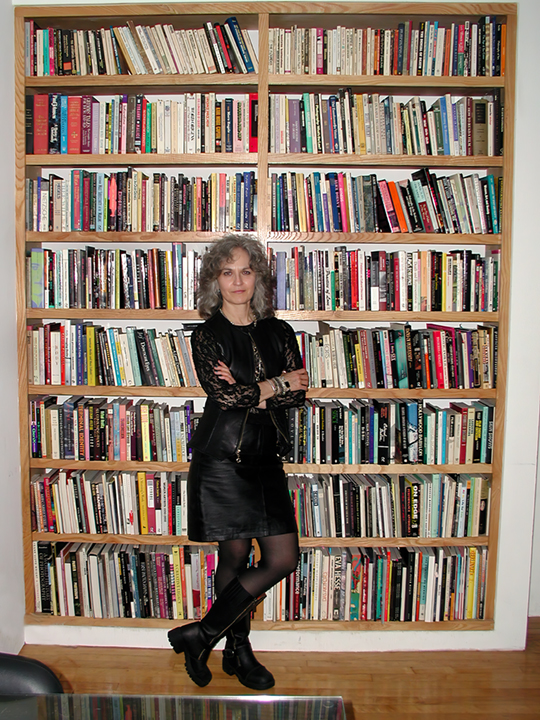

Barbara DeGenevieve’s Teaching Philosophy

I have been involved in undergraduate education since 1980. Times have changed. The political culture has changed. Things that would never have crossed my mind in 1980 are at the forefront of my thinking now. My job is no longer to simply mentor students technically, conceptually and theoretically; they now need to be prepared for the realities of the art world, the work place, and the greater public realm. This was perhaps always the case, but for most artists older than 30, it was something learned individually through experience, not discussed in the classroom of non-commercial art schools. This is not about being co-opted or selling out. It’s not about being less of an artist. It’s about understanding the realities of the art world as well as that other, much bigger world.

So then what is my responsibility as an educator?

There are three things at this point in time that are an absolute priority, and in the best art programs, have become a given:

1. A commitment to diversity in the student and faculty population. This comes with an equal commitment to a diversity of issues being addressed including the racial, cultural, political, social, sexual and personal.

2. A commitment to a rigorous theoretical grounding that covers the broad terrain of contemporary practice as well as the current thought specific to a media based practice.

3. A commitment to an interdisciplinary education for artists.

The need for these three are indisputable, and so with that said, there is another area that has become increasingly important to the education of artists but has not been treated with the same kind of focused attention. That is preparation for life after school.

Academic art institutions have traditionally ignored the need to prepare students for two important things:

+ The business of being an artist

+ And other options they might have in applying their abilities as an artist to another career path.

Artists are trained to be thinkers – visually literate, critically and culturally aware. These are enormously valuable qualities in any profession or job situation. I am interested in providing students with the skills they need to both become the art star everyone hopes to be and/or the successful professional in other related or unrelated realms. The importance of a strong studio education is uncontested. However, it needs to be supplemented with the skills necessary to sustain the talents of the artist, in other words, a reality based grounding in combination with the aesthetic, poetic, and conceptual. The better balanced an individual is in relation to their talents and skills, the better chance they have of being successful. If an institution can provide young artists with the tools they need for plasticity and flexibility, there is a better chance that more will continue in the arts and arts related fields, and those who choose other career paths will be creatively and conceptually engaged.

Whether we’re comfortable with the changing economies of culture and the marketplace, the reality is that students need to be prepared for the current social climate, and it is the responsibility not only of teachers but of the institution to provide an education that will help them navigate and negotiate an often unpredictable territory.

Even though we’re most familiar with art as an internal experience, the artist is also a functioning individual in a social arena – the artist as a public figure – the artist as a citizen. Artists so often think of themselves as outsiders and therefore believe themselves to be outside of the restrictions of the greater culture. “I’m an artist – I can do whatever I want.” That may be the case, but there may also be consequences to one’s actions. How an artist interfaces with the rest of the culture is becoming more and more important in a time of law suits and determinations of responsibility.

There were 2 incidents in 2003 at SAIC, that brought this issue to a head – one grad and one undergrad. In 2002, the administration of the school instituted a walk through after the MFA and BFA shows are installed, but before the opening, to check for anything that might involve them in a law suit. They found 2 projects that were potentially problematic, one involving public safety and the other involving ethics and privacy rights. Two grad students were working collaboratively on a project that included a slightly scaled down model of stadium bleachers on which the audience was to sit. In the case of the undergrad, an internet piece had been produced that used sexually explicit images pulled from international tele-conferencing sessions he had conducted on the internet. Both were tagged by the administration and neither would be allowed to be exhibited until and unless certain criteria for safety and legality were met. This created controversy and cries of censorship.

Out of the disruption, student meetings, and protests with which I became involved as the chair of the faculty senate, I realized how unprepared the institution was to deal effectively with these situations. Aside from not having a mechanism in place for an expedient resolution to the problems, students were not being prepared to understand the potential consequences of their work. With 5 days left before the opening of the thesis shows, it was a bit late to start that important discussion. These incidents created a great deal of dialogue among faculty and students about these issues, but there needed to be an ongoing institutional discussion. I proposed a panel to address what had happened and to be an informational forum for better understanding these problems. It turned into a series of 3 panels that developed a list of questions students were asked to consider and experts were asked to answer. They involve three areas: Health and Safety, Censorship and the Law, and Ethics.

Health and Safety

+ What are the basic principles that should guide an artist when planning for a public presentation of her/his work?

+ Should an artist disregard those principles for artistic/conceptual reasons (such as their work is about danger). Will their art still be viable?

+ How should the ADA (American Disabilities Act) guide artists in planning for public exhibition?

+ Should viewing heights be considered in regard to viewers in wheel chairs?

+ Are there special safety concerns for interactive works?

+ What are the limits of responsibility for safety of an audience?

+ Are there special concerns to keep in mind for children in our audiences?

+ What responsibility does the audience bare for their own safety?

Censorship and the Law

+ What does the first amendment mean for artists?

+ What principles guide determinations of copyright infringement?

+ How important are photo releases for photographers, film and video makers?

+ Are photo releases required when taking images in public space?

+ How should privacy rights guide our artistic endeavors?

+ What are the current guiding tenets for cyber art?

+ When an artist feels their work might be in a legal gray area, where can they go to address the potentially problematic issues in their work?

Ethics

+ Are there general tenets of ethics that should guide an artist’s work?

+ If one of the functions of art is to push us to re-think our lives and the culture we live in, are there any moral or ethical limits to this strategy?

+ When the work can be seen as offensive, pornographic or unethical, does the artist have a responsibility to foresee reactions to their work?

+ For many people in the arts, offensiveness or danger is not a moral or ethical issue. But what happens if the artwork becomes available to a public that is not usually a part of the art world environment (those who go to museums, read art magazines)?

+ What is an artist’s responsibility to the public?

The dictates of cultural life in the 21st century have modified or shaped everything described above. The things that have remained constant, and I am determined will never change, are my basic rules for teaching:

- Give students the conceptual and technical tools they need to be good artists.

- Give students the information they need to stay out of trouble or to at least make an informed decision about the responsibility they must take for their actions.

- Treat your students with respect, regarding them as artists, not simply as students.

- Engage them in considering ideas they may not be comfortable with.

- Never be easy on them; push them as hard as you can, then push them to go farther.

- Challenge students to be critical of what they’ve done, especially when their ideas seem most resolved.

- Provide a classroom environment in which anything/everything can be discussed.

- Share everything you know; make generosity attractive

- Make critical thinking something they demand of themselves.

- Help them to trust themselves.

- Make them unafraid to risk everything.

)